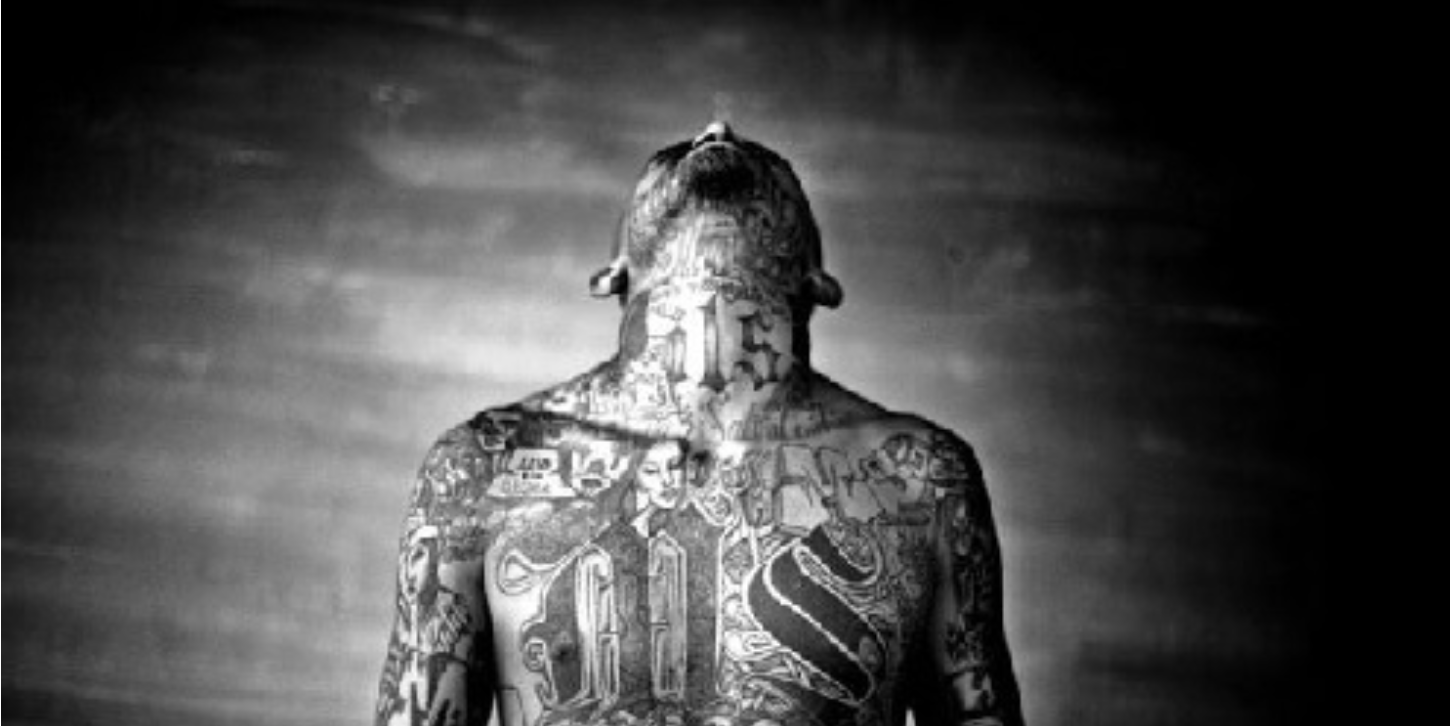

How a street gang grew into a transnational criminal organization and now threatens international stability

In June 2015, a federal judge sentenced three gang leaders to prison for a nearly three-year spree of murders and beatings in the Washington DC area. Among the many victims was a 14-year-old whom the gang members stabbed to death. The three gang leaders were members of the violent Mara Salvatrucha gang, also known as MS13.1 MS13 is so large that it has been officially labeled a transnational criminal organization and a threat to international stability. Its actions have helped make the Northern Triangle—Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—the most violent region in the world that is not currently at war.2 The activities of the gang, ranging from drug trafficking to extortion, continue to threaten the security of the United States and its Central American allies. To counter the threat, the United States should commit more resources towards the fight against crime in Central America and expand efforts to address its underlying economic and social causes.

The Growth of MS13

MS13 originated in Los Angeles in the 1980s. A refugee crisis, stemming from civil wars in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, sent a number of immigrants to the Los Angeles area. There, veterans from the civil wars—including former guerrillas and Salvadorian government soldiers—organized themselves into competing criminal groups.3 The strongest of these groups became known as Mara Salvatrucha. In Central American Spanish dialects, “mara” means gang, “salva” refers to El Salvadorian nationality, and “trucha” is slang for clever or sharp.2 While originally all members of the gang were El Salvadorian and lived in Los Angeles, MS13 quickly expanded into other nationalities and US cities, garnering a reputation for its excessively violent methods, such as execution by machete. It received protection and material support from the Mexican Mafia, and provided hit men and other services in return.2 Mara Salvatrucha then added the “13” to its name to become MS13—“13” is the numerical position the letter “M” holds in the alphabet.

Expanding with Unwitting US Help

The deportation strategy employed by the US against MS13 had the unintended effect of turning the gang into a transnational threat. In the 1990s, the United States realized that MS13 was growing into a substantial threat. In response to violence by MS13 and other criminal groups, Congress passed the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. This law expanded the number of crimes for which an immigrant could be deported and criminalized a wide range of behavior.4

Consequently, the United States began deporting a large number of individuals associated with the gang back to their home countries. Between 2000 and 2004, the United States sent around 20,000 criminals back to the Central American countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.2 These Central American governments, some of the poorest and least stable in the Western Hemisphere, were incapable of dealing with the influx of criminals. Gang members from the US found it easy to build their criminal networks in their home countries. These individuals kept contact with other gang members in the United States and began to work across national borders. Rather than stopping the gang, US efforts only helped it to expand internationally.

MS13 has ambitions to grow even beyond its current reach of power. The gang currently has members in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. It has expressed a desire to expand into Chile, Peru, Spain, Argentina, and other countries. According to a report by the International Assessment and Strategy Center, MS13 gang members facing deportation may have instructions to lie about their countries of origin, thus obtaining “free rides” to those nations targeted for expansion.5

MS13 has also worked with Mexican cartels to accomplish its goals. Together with the Los Zetas Cartel, it has partitioned off control of the Central American migrant route. In turn, it relies on the cartel’s human trafficking networks to move its people quickly into the United States. MS13 has also obtained sophisticated weapons—LAWs, RPGs, SAM-7s—and sells them on regional arms markets to other criminal organizations.5

The Threat Posed By MS13

MS13 represents an immediate threat to US and international security. The gang has approximately 30,000 members in Central America and at least 8,000 members operating in 40 different US states and Washington DC.6 In 2013, it became the first street gang to be designated by the Department of the Treasury as a Transnational Criminal Organization. In 2008, FBI labeled the threat level posed by MS13 to the entire United States “medium” and labeled the threat in gang-concentrated areas “high.” FBI reported that the organization was involved in a variety of criminal activities, including drug trafficking, human trafficking, murder, rape, prostitution, home invasions, immigration offenses, kidnapping, carjackings, and vandalism.7

MS13 poses an even greater threat to public order in Central America than in the United States. In large part because of gang activity, Central America’s homicide rate is four times the global average. The number of incidents of robberies, extortion, human trafficking, and kidnappings have all increased in recent years.8 In El Salvador especially, this is due to the actions of MS13.

MS13’s Structure

The Mara Salvatrucha gang has a decentralized command structure which makes it much more difficult to take down than the traditional criminal organization. The gang is comprised of a loose network of criminals connected across numerous countries. While the gang often conducts sophisticated operations, it lacks unified motives and command structures. It is composed of hundreds of “cliques” that function as smaller gangs with their own leadership structures and goals. These “cliques” do occasionally work together but mostly operate independently. Law enforcement cannot simply neutralize gang activity by arresting gang leaders; in fact, the gang is almost entirely unaffected when it loses some of its leadership.

MS13 has proven its ability to learn and adapt to law enforcement methods. It recruits a large portion of its members from disenfranchised and impoverished youth in Central America.9 In recent years, MS13 has also become a political actor in El Salvador, has attempted to influence elections there, and has made political agreements with the national government.10

There can be little doubt that the problems facing Central America are also the United States’ problems. The convergence between organized crime and terror is an imminent vulnerability—criminal networks can move almost anything through their smuggling routes. It would take only a simple bribe or a tunnel under the US border for MS13—or any other criminal organization south of the US border—to bring terrorists into the country. Additionally, international drug traffickers have a presence in nearly 1200 American cities and routinely commit violent acts on US soil.8 Because MS13 operates inside the United States, it represents a direct threat to public safety.

Ganging Up Against the Gang

The root problems behind the creation and growth of MS13 are undoubtedly economic and social. According to USAID, the chief United States foreign aid department, El Salvador has three major problems: “poor education quality, resulting in a growing number of youth leaving school without basic skills mastery; limited access and inequity for disadvantaged groups such as indigenous girls, urban and rural poor, and minorities; and unemployed youth who are highly susceptible to gangs, crime, and poverty.”4 El Salvador and other Central American countries need to address the underlying social factors that facilitate the flourishing of gang activities in the region. These nations must also win the battle in the minds of innocent bystanders. If Central American governments can convince their people to rally behind them, MS13 activities will die without the support of the people. Full public support is the first step in the war against organized crime.

To this end, the United States has initiated programs to assist struggling governments south of its border. One important program is the Merida Initiative (also known as CARSI). The Merida Initiative, passed in 2007, allocates $1.4 billion towards assisting Mexico and Central America in combating drug trafficking, drugs, and organized crime. These funds are used to pay for equipment—aircraft, weapons, boats, inspection technology, canine units—technical advice, and law enforcement training.4

So far, the results of the program have not been reassuring. Criminal activity has only increased in Central

America. This is partly due to inherent problems in the Merida Initiative. Each US agency has its own mission, priorities, and strategies. Instead of working together, agencies often “engage in turf battles” over jurisdiction and differing strategies.4 The program also has no concrete deadlines or comprehensive strategies. Policymakers should work to solve these problems and ensure that US agencies work together under a unified Merida Initiative strategy. Perhaps policymakers should also consider partitioning some of the funds from the Merida Initiative towards addressing the social and economic problems in the Northern Triangle. At the very least, USAID should invent new programs and strategies to assist Central American nations in their struggle against corruption and poverty.

Ultimately, the solution to MS13 will require a great deal of cooperation between the United States and Central American countries. While the United States has made some progress with the Merida Initiative, it needs to do more if it wants to make an impact against organized crime. El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and other Central American countries must also commit to solving their own economic and social problems. This will have to begin with a complete overhaul of their respective law enforcement, court, and prison systems. Corruption too often paralyzes local government law enforcement efforts.8 Unfortunately, the security services of these nations are often too small and underfunded to combat ruthless gang leaders effectively. They cannot win the fight against organized crime alone; indeed, they must openly invite the support of other nations if they wish to restore order within their borders. The United States should be the first to lead this initiative and bring these nations together to win the war on crime. ■

- Spencer Hsu, “Three MS-13 Gang Leaders Sentenced in Brutal Killings, Attacks Across D.C. Area,” Washington Post, 23 June 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/crime/three-ms-13-gang-leaders-sentenced-in-brutal-killings-attacks-across-dc-region/2015/06/23/72dc9630-19b7-11e5-bd7f-4611a60dd8e5_story.html.

- “MS13,” InsightCrime, http://www.insightcrime.org/el-salvador-organized-crime-news/mara-salvatrucha-ms-13-profile.

- Celinda Franco, “The MS-13 and 18th Street Gangs: Emerging Transnational Gang Threats,” Congressional Research Service, 30 January 2008, http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/102653.pdf.

- MaryKathryn Barlean, “Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13): The Imminent Threat Inside Our Borders and Throughout the Continent,” Western Oregon University, June 2014, http://digitalcommons.wou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=honors_theses.

- Douglas Farah and Pamela Philips Lum, “Central American Gangs and Transnational Criminal Organizations,” International Assessment and Strategy Center, February 2013, http://www.strategycenter.net/docLib/20130224_CenAmGangsandTCOs.pdf.

- “Treasury Sanctions Leadership of Central American Gang MS-13,” US Department of the Treasury, 16 April 2015, http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl10026.aspx.

- “The MS-13 Threat: A National Assessment,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, 14 January 2015, https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2008/january/ms13_011408.

- Roger Noriega and Jose Cardenas, “To Secure Southern Border, US Must Lead International Effort to Stabilize Central America,” American Enterprise Institute, 24 July 2014, http://www.aei.org/publication/to-secure-southern-border-us-must-lead-international-effort-to-stabilize-central-america/.

- John Fitzpatrick, “Globalization – the Beginning and the End of MS-13?,” Global Security Studies, 4, Issue 4, Fall 2013, http://globalsecuritystudies.com/Fitzpatrick%20MS13-AG.pdf.

- Douglas Farah, “The Transformation of El Salvador’s Gangs into Political Actors,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 21 June 2012, http://csis.org/files/publication/120621_Farah_Gangs_HemFocus.pdf.

Fall 2015

Volume 17, Issue 6

9 November