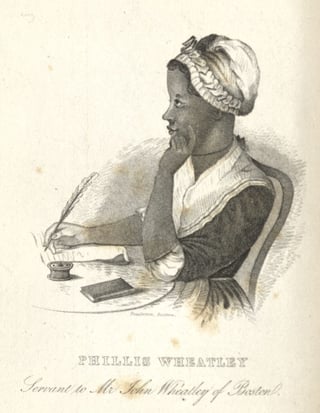

One midsummer day in 1761, John Wheatley arrived at a Boston auction block in want of a slave girl. She would be a gift for his wife, Susanna, to help with domestic work. The girl he picked was frail, somewhat sickly, and no more than seven or eight years old.

She had just arrived from the west coast of Africa, likely Senegal or Ghana, and was named after the ship that brought her: Phillis.

As was customary for slaves at the time, Phillis adopted the Wheatley’s last name.

Though John purchased Phillis with the intention of attaining a domestic slave, after a few short weeks, he and Susanna soon found she had a remarkable aptitude for learning. In fact, she so thrived in her studies, her new masters introduced her to ancient literature including classical myths and epics, and—after teaching her English—trained her in Latin and Greek. Today, these subjects might be called, "The Classical Liberal Arts." Wheatley also found great joy in reading the Bible, and soon committed her life to Christ. She also studied geography and astronomy. All these things took place within the first sixteen months of commencing her new life in America.

What surprised her new masters was not only her knack for learning but her attentiveness to nuanced literary techniques—especially in poetry.

At thirteen, Wheatley wrote her first poem, “To the University of Cambridge in New England,” which was later published in a larger compilation of poetry.

Despite her good relationship with the Wheatley family, her health eventually took a significant turn for the worse. When she was approximately eighteen, she departed with her masters’ son, Nathaniel, on an extended trip to London upon her doctor’s recommendation. She wrote to a friend shortly after she arrived of the “unexpected and unmerited civility and complaisance with which I was treated by all.”

During her stay in England, she continued to write extensively under the patronage of Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, and eventually published her first book of poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Wheatley was only nineteen years old. As the compilation eventually began to make waves in both England and America, Wheatley returned to Massachusetts.

During her stay in England, she continued to write extensively under the patronage of Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, and eventually published her first book of poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Wheatley was only nineteen years old. As the compilation eventually began to make waves in both England and America, Wheatley returned to Massachusetts.

Of course, America in the late eighteenth century was not yet accustomed to African Americans as authors—to say nothing of a female African American. In fact, when Wheatley published her book of poems, she became the first slave in American history (and the third female) to do so. While her poetry was generally well-received, the book contained a preface in which seventeen men from Boston, including the soon to be declaration signer John Hancock, confirmed that Wheatley did indeed write each poem. Otherwise, the publication likely would have been received as a hoax — perhaps someone posing as a female slave for propaganda purposes.

Wheatley modeled her poetry largely after acclaimed English poets including John Milton, Thomas Gray, and Alexander Pope. She also often employed allusions to classical mythology and Scripture.

In 1775, Wheatley wrote a handful of poems in honor of the then military commander George Washington. The following year, she received an invitation to meet him at his Cambridge headquarters, which she gladly accepted.

Washington at one point praised her, saying, "the style and manner [of your poetry] exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents." Later, Thomas Paine published her 1775 poem “To His Excellency, George Washington” in the Pennsylvania Gazette.

At some point during these years—historians are unsure of the exact date—the Wheatleys freed Phillis from her legal role as their slave.

Over the years, Wheatley continued to write more extensive poetry focusing primarily on themes of anti-slavery, democracy, and the Christian faith. She found herself increasingly in the public eye after the publication of her poem "On Being Brought from Africa to America.” The closing two lines became popular for their overtly political and moral statement on equality for African Americans:

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

"Their colour is a diabolic dye."

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

Though her fame continued to grow, Wheatley found herself devastated at the death of her only teacher and mother figure, Susanna, in 1774. John Wheatley died only four years later. These two tragedies scared Wheatley deeply.

Yet all was not lost. In 1778, she married John Peters, a free African American grocer. Though the two were somewhat happy together, unfortunate circumstances continued to plague them both. Before long, they had three children but lost them all in infancy. And since neither Wheatley nor Peters was in possession of much money, they were forced to live in extreme poverty.

Wheatley, of course, kept writing poetry. Unfortunately, she was unable to publish a second volume without further patronage from Countess Selina Hastings. Growing tensions surrounding the War for Independence reduced her reader base as well, and despite her best efforts, Wheatley found no one willing to sponsor her work.

Her marriage struggled more than even under increasing economic strain until Wheatley was forced to work as a wash woman, or scullery maid, in a local boarding house where conditions were unthinkably dirty.

.jpg?width=440&name=This%20statue%20of%20Wheatleyis%20a%20part%20of%20Boston's%20Women's%20Memorial%20(1).jpg) Peters was eventually incarcerated in 1784 for complications relating to his debt, and Wheatley was left without any connections or relations save one sickly infant son. She died on December 5 of that same year.

Peters was eventually incarcerated in 1784 for complications relating to his debt, and Wheatley was left without any connections or relations save one sickly infant son. She died on December 5 of that same year.

Though Wheatley’s story concludes tragically, she stands out in history as a profound example of what incredible feats African Americans might have accomplished in the colonies if only they were afforded the opportunity. While the majority of white Americans’ sentiments towards African Americans were disparaging at best — and abhorrently abusive at the worst — the Wheatley family is an example of outliers who treated Phillis with dignity and respect and believed in her ability to succeed not only within the home but within the larger society as well. Today, she lives on as an inspirational figure in American history.

We appreciate Wheatley's legacy as it put on display the possibility of freedom and thriving not only for her contemporary African American slaves, but for all American women as well.

---

With the Classical Liberal Arts method, we value learning how history has influenced our current society. Click the button below to check out our history major.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, and Lynn Dumenil. Through Women's Eyes: an American History with Documents. 4 ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2015.